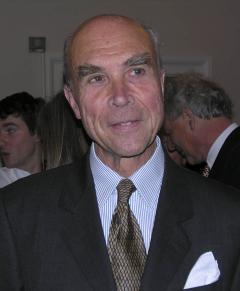

A Man for All Seasons: Aubert de Villaine of Domaine de la Romanéee-Conti

POSTED ON 17/05/2010Since the Decanter Man of the Year Award is notable for the quality of the party thrown by the winner of the award, it seemed like a grievous oversight that until this year the magazine had never once given the gong to a Burgundian. I thought it was high time there was some decent wine to drink at the party so when last autumn I suggested somewhat tongue in cheek to Sarah Kemp that the obvious candidate for the award was Aubert de Villaine of the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, I hardly thought that she would take me up on the suggestion.

Aubert de Villaine, hero of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti

Aubert de Villaine, hero of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti

Ok, I know, it was in fact an august panel of wine brahmins (excluding myself I hasten to add) who chose Aubert de Villaine but at least I was invited to the party, a Mosimann-catered dinner at Corney & Barrow last week. And we did drink one or two wines that were a marginal improvement on the usual fare drunk in the Rose household. Romanée-Conti for instance, a wine I have never drunk before in my life because it’s a little out of my price range.

In the panoply of fine wine, the DRC represents the pinnacle not just of great burgundy but of great wine itself, and the DRC more or less defines the elusive concept of terroir which any serious producer, New World or old, aspires to emulate. The DRC is not a concept or a cult wine and if it’s an icon, which I suppose it is, it’s an icon for the best of reasons, for the only reason really why wine should ever be allowed to call itself an icon: because it’s earned its stripes over time.

Some might say that the DRC was already a great estate when the urbane, tweedy Aubert de Villaine took over in 1974 (with Lalou Bize-Leroy), so why give an award to someone who’s just continued to do what’s always been done? But it wasn’t consistently great at the time. Nor does terroir, no matter how good, exist in a vacuum. If the potential is there, it still needs the alchemy of vision and application to interpret it and turn the base material into gold. Acting as custodian for past and future generations, Aubert de Villaine has steered the DRC, now biodynamically farmed, to its position of pre-eminence in the world of wine by virtue of researching the terroir, through rigorous vine selection and trials, and meticulous attention to detail in the husbandry of the estate.

Decanter supremo Sarah Kemp with Christian Moueix

Decanter supremo Sarah Kemp with Christian Moueix

Attended by a phalanx of burgundian and other luminaries, the evening started on a stylish high note with magnums of 1997 Salon, wonderfully fresh and citrus-crisp with underlying toasty bottled-aged notes just starting to develop. We sat down to a glass of 2003 Le Montrachet to accompany Mosimann’s shockingly delicious warm Scottish lobster in beurre blanc. It was as evolved as you’d expect from this torrid vintage, rich, golden, buttery, nutty and unctuous, full-flavoured yet with a freshness which, though it might not carry the wine to a great old age, nonetheless defied the elements in this most Californian of Burgundy vintages.

Lalou Bize Leroy

Lalou Bize Leroy

The first glass of the 1991 La Tâche smelled a shade gamey, but no more so than I would have expected. Nevertheless, Jean-Charles Cuvelier, the estate’s director sitting on my left ordered up another bottle as he wasn’t entirely happy with the first bottle. I managed, with some difficulty, to hold on to my glass, whereupon the second bottle arrived. Generously I thought, I allowed half the table to compare my glass of the first La Tâche with their second glass.

Simon Loftus of Adnams

Simon Loftus of Adnams

Relatively deep coloured for a near-20-year-old pinot noir, it was just a touch fresher on the nose, with a fragrant incensey quality that demanded your nose’s attention for quite some while before you even thought of drinking it. But the moment had to come and the result was sensational, the quintessence of everything you always dream that red Burgundy should be, voluptuous in the sheer purity of its red berry flavours and silky texture, sweetly sumptuous, delicate and fresh at the same time, sheer hedonism in a glass.

I almost forgot my roasted tenderloin of veal but managed a melt-in-the-mouth mouthful before moving on to the 1971 Romanée-Conti, the vintage of his marriage to Pamela. As I have never drunk Romanée-Conti before, the expectation was huge but there was no let-down. Words can no more do justice to a wine like this than an attempt to describe the effect of a Verdi aria in words. Fragrant yes, ethereal yes, those things and more. Showing a touch of garnet but still remarkably youthful looking, here too there were notes of game and incense in the fragrance, and then a gorgeous, lingering sweet pristine fruit quality with the texture, delicacy and grandeur of a wine that sings its own aria.

An homme de terroir

An homme de terroir

The quantities were, not surprisingly, limited but at no point in time was there any sense of parsimony or that you needed more. All of us present were content to swirl and sniff for as long as it took to drown our senses in the amazing aromas of these great wines. When we drank, we sipped, not because we were being parsimonious but because that’s the only way to drink wines like this, slowly savouring every detail, allowing the wines to take over your senses and etch their subtle character into your memory. It’s easy to go over the top about wines like this because they do make a powerful appeal not just to the senses and the grey matter but to the emotions as well.

On presentation of the award, a decanter, Aubert joked that he never decanted his wines. Modest yet proud, intellectually rigorous and warm , he went on in typical self-deprecating manner, 'I want to share this award with you. If Burgundy is doing well today, and quality is higher than ever, it is because of our return to the values that made it famous – the values of terroir. Thirty years ago, terroir was disregarded. Today it is seen as a goal by wine regions across the world.'

‘The DRC is like a ship going forward but that carries a past that is rich, alive and enriching’, he said. Where tradition can be an excuse for resting on laurels, he make it clear that ‘without less of a past, we would have no direction’. Acknowledging his debt both to his ancestors, the founder and his grandfather, he said ‘it was my father who taught me everything and left us a compass which allows us to take the ship in the right direction, towards a goal worthy of their vision’ and to today’s workers who put their philosophy into everyday practice. ‘It is with hesitation and suffering that I accepted this award’, he said, and as the eye twinkled at the words, the room erupted into laughter.

We happy few © Decanter

We happy few © Decanter

It was a hard act to follow and to our pleasant surprise we were treated to a palate refresher of the 1997 Salon Champagne before moving to the English cheeses accompanied by a fine Bourgogne 1991 and a glass of the great 1963 Fonseca vintage port.

The unspoken words at my table and I suspect most tables were over questions of money. Too vulgar on a night like this to talk about money and price. And yet how can you consider DRC without acknowledging that fact that the most coveted of wines also makes it the world’s most expensive. Needless to say, words like value are otiose because value no more enters into the equation than it does in the consideration of any icon whose demand far exceeds its supply. So it is with the DRC. On my way to the tube afterwards, someone asked me if I realised that I’d just drunk a glass of a £7,000-plus bottle wine. At the back of my mind, I knew I had, but I didn’t want to think too hard about that. The experience, and it was an experience, was enough.

Robin Kernick, former Clerk to the Royal cellars

Robin Kernick, former Clerk to the Royal cellars

The DRC in numbers

The Domaine de la Romanée-Conti is owned by the de Villaine and the Leroy families. It consists of 7 grands crus as follows with details of the 2007 vintage as at January 2010:

1.Average vine age 2. Av prod.(cases) 3. Total prod. 4. Yield

Echézeux 1. 35 2. 1340 3. 1233 4. 26

Grands Echézeaux 1. 55 2. 1150 3. 754 4. 31

Romanée-St-Vivant 1. 37 2. 1500 3. 1165 4. 28

Richebourg 1. 45 2. 1000 3. 1136 4. 32

La Tâche 1. 50 2. 1870 3. 1403 4. 27

Romanée-Conti 1. 56 3. 450 3. 400 4. 26

Le Montrachet 1. 65 3. 250 3. 316 4. 38