Una, Dos, Tres, Cuatro. Blending Palmas with Gonzalez Byass

POSTED ON 15/11/2012

After a summer abnormally dry even by Andalucian standards, the hardy Payoyo goats of the Sierra de Grazalema Natural Park were foraging for food. Dark storm clouds gathered over the mountain peaks as the driver took the winding road down to Jerez de la Frontera.

From the small square behind the Hotel Palacio Garvey, melancholy strains of flamenco drifted up past the palms through my window. It may not have seemed like manna to the scattering crowd outside but when the heavens opened, that’s exactly what the torrential rain was to the region’s sherry producers.

At the Bodega

At the Bodega

It’s not just the vineyards of Jerez that have suffered from drought. Thanks to systematic price-cutting by the Rumasa group in the 1970s, sherry itself has been in long-term decline. Its plight was not helped by the long-term fight to have the name sherry restricted to the produce of Jerez.

Since the mid-1980s, the vineyard area has been reduced by half. Only recently has there been something of a fightback, first with the idea of vintage-dated sherry and then in 2000 with the Consejo Regulador’s creation of the VOS (Very Old Sherry) and VORS (Very Old and Rare Sherry) categories.

More recently still, after Lustau launched its range of premium almacenista sherries, other companies such as Barbadillo and Hidalgo began to come up with innovative ideas. Once such concept was en rama, a raw, unfiltered dry manzanilla sherry from Barbadillo.

Other sherry firms followed suit, notably González Byass , Hidalgo, Delgado Zuleta, Sanchez Romate, Williams & Humbert and Equipo Navajos. Another recent innovation is González Byass’ Palmas range and it was for the Palmas that I found myself in Jerez.

Antonio Flores

Antonio Flores

After a swift, strong coffee next morning in a local bar, I strolled along the ancient city’s cobbled streets via the bustling fish market and the Virgin Mary shop to the González Byass bodega. Past security and inside the wrought iron gates, my host Martin Skelton, managing director UK of González Byass, introduced me to the master blender, Antonio Flores Pedregosa.

I had been invited to help Antonio blend the four special Palmas finos. This was to be only their second launch and not an invitation to be refused lightly.

Antonio’s father Miguel, started working when he was 14, became head winemaker at González Byass before him, and was pensioned at 70. The family were given an apartment in one of the old streets above the winery, so to say that Antonio was born into the sherry trade is literally true.

Palmas in the Archive

Palmas in the Archive

He had been with the family company making wine since 1 September 1980, so, no matter how flattering the suggestion therefore, the idea that I might actually ‘help’ a man of Antonio’s vast knowledge and experience to blend these unique wines verged on the risible.

Balding, bespectacled, affable, Antonio was clearly as well-acquainted with the liquid inside every barrel in the sherry bodega as if each cask were one of his offspring. And it was true in a manner of speaking, because each barrel of wine had indeed had been carefully raised and nurtured by him.

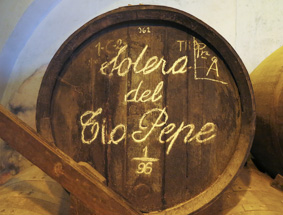

Although my help was not really needed, it was an honour nonetheless, to have been invited to join him in his quest to pick the eyes out of the Tio Pepe solera for Palmas. I was looking forward at least to playing a walk-on part, my appetite whetted by a cursory review of the extensive family archive of handwritten records.

Tip Pepe

Tip Pepe

González Byass produces a wide variety of sherries of different ages, but Tio Pepe is its bread and butter. To make this appetizingly dry style of fino, Antonio needs to know the character of each solera and blend them together in such a way as to manage, evolve and maintain a consistent house style.

21,750 casks of Tio Pepe are divided between 22 soleras, each of which is made up of a number of barrel rows, and each of these in turn comprises groups of individual sherry casks. The younger wine sits in the upper tiers. As the wine in the lowest, the solera itself, is drawn off and bottled, the upper tier casks are replenished.

The four Palmas are a limited edition drawn from the best Tio Pepe casks. Flor, the protective veil of yeast that lies on top of the wine in the barrel like a sheet of clingfilm, is what gives fino its special savoury character. The yeasts feed off the nutrients in the alcohol, while tiny amounts of oxygen seep through the wood, helping the them develop proteins which bond to isolate the wine from the air above it.

Selecting the Palmas

Selecting the Palmas

When the flor keeps going longer than usual, the cask receives a hand-drawn mark, curved to form the spine of the palm branch. Additional marks showing longer ageing create the shape of a palm leaf, hence Palmas. For Una, Dos and Tres Palmas, there are 146 casks aged six, eight and 10 years.

Antonio has already pre-selected 20 barrels of each age category. To brighten up this dreary autumn morning, the job in hand is to taste the 60 pre-selected barrels and whittle them down to the best. As we enter the dark, tall bodega with its invitingly bready, balsamic smells, we spot the mouse ladder and an emptied glass on the floor, but no sign of a drunken mouse weaving uncertainly towards its hole.

Antonio removes a bung from a sherry butt. Inside, the white coating of flor looks like an old man’s wrinkled skin. He plunges his venencia, the small vessel at the end of a long rod, through the yeast, pulls out a draft, deftly pours it from on high into my outstretched glass and we taste.

Flor yeast in the cask

Flor yeast in the cask

Two bodega staff precede us, drawing sherry from the pre-appointed casks and handing the venencia to Antonio. We taste, first of all hesitantly, then, as we grow accustomed to each other’s rhythm, we pick up the pace. For Una Palma, we look for the freshest, most elegant finos, for Dos Palmas, those with a touch more concentration and nuttiness. It’s surprising how much each barrel varies in taste, each row in style.

By the time we get to the Tres Palmas, Antonio says we’re looking for the subtle effects of the oak that bring buttery notes and weight. It’s enormous fun and I want to linger, but after 60 samples from barrel, we’ve whittled it down to 30, 10 for the first three Palmas. With only six barrels in the Museo Solera, samples for the Cuatro Palmas will be tasted in the tasting room.

Here we try firstly the 10 samples for Una with the aim of picking our favourite four. We’re agreed on two, differ on two. I cede to Antonio. For Dos Palmas we're looking for the pastry notes of the flor and agree on the four best. Then we come to Tres. Eliminating any wines that lack elegance, we agree on those with undertones of walnut and good concentration of flavour and character.

Antonio Pours

Antonio Pours

Finally to the six barrels of Cuatro, all effectively bronze-hued amontillados. We choose the most nutty, complex and intensely concentrated. At 3pm, job done, we repair to Arturo’s for some of that divinely fresh baby sole and snapper I’d seen in the fish market earlier.

By the evening, Mauricio González-Gordon, the head of the company, has returned from Madrid and he’s eager to try the new blends. We discuss the problems of the long-term decline of the sherry industry and he tells us how González Byass is keen to be in the forefront of the revival. His company had already launched a successful en rama, or raw, unfiltered sherry to coincide with the family company’s 175th anniversary.

In line with the tapas bar revolution and the growing vogue for interesting new styles of dry sherry, the Palmas range of individually selected sherries is part of his attempt to remind consumers that sherry is not just a standardized product.

‘Palmas is as far as you can get from unfortunate bland associations of sherry’, says Mauricio. ‘It’s a discovery for consumers and every year there are new people coming into sherry who don't think of it as an old-fashioned drink for vicars and maiden aunts. Fino is made to be drunk with food and new consumers are enjoying the fun of trying it with different types of food.’

Picasso was Here

Picasso was Here

Over dinner, we put his words to the test by drinking the four Palmas selected that morning in the bodega. Mauricio doesn’t say much but his broadening smile speaks volumes. So if there’s anyone out there looking for a novice sherry blender, you know who to ask.

The Palmas will be on sale this month through the Wine Society, Justerini & Brooks, Berry Bros., Lay & Wheeler and Lea & Sandeman with recommended prices in ascending order of £12.49, £16.99, £36.99 and £51.99.. For more details of González Byass, check them out online at http://www.gonzalezbyass.com/

The Bodega mouse will be here

The Bodega mouse will be here