Cape Crusaders

POSTED ON 19/05/1999Not before time, a number of pioneering new wine projects have begun to sprout out of the Cape's fertile vineyard soil. The ostensible aim of the partnership between black and white is to give disadvantaged communities a stake in the wine industry, with a share in the profits and ownerships. But is there real substance behind these laudable joint ventures? Or do they amount to little more than window-dressing, allowing white owners to help themselves to a more lucrative slice of the expanding international market?

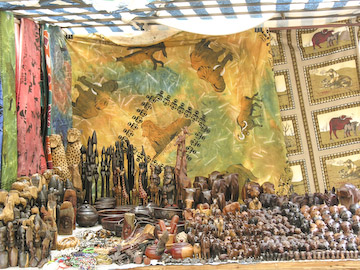

It's a jungle out there

It's a jungle out there

The Rev Trevor Steyn of the Anglican Social Development Institute was in London last month as a guest of South African High Commissioner Cheryl Carolus to launch a Chardonnay and Pinot Noir under the Thandi name (available at Tesco). Thandi was set up in 1994 as a profit-sharing venture involving some 60 families in Lebanon village, wine producer Paul Cluver's estate and the South African Forestry Commission (Safco). The aim was to establish a successful business which would be a model for disadvantage black rural communities.

How does it work? Using Paul Cluver's winemaking facilities and the marketing power of the giant Stellenbosch Farmers Winery (SFW), it employs 14 full-time staff who are assisted by seasonal workers who help with harvesting, planting and in the winery. A black winemaker, Patrik Kraukamp, receives supervision from Andries Burger, Cluver's winemaker. There are currently 14 hectares of vineyard, three-quarters Chardonnay, one-quarter Pinot Noir. The aim is to plant a further 70 of mainly Sauvignon Blanc, Cabernet and Merlot and to build a new winery by 2003.

It hasn't all been plain sailing, as the Rev Steyn explained. There has been a chronic lack of self-confidence among the downtrodden black community. But Steyn is a realist. He recognises that empowerment is a long, slow process, starting with helping the black community to take responsibility and achieve a sense of dignity. He and Cluver were uncomfortable with the SFW's apparent desire to control the project's destiny as a quid pro quo for its development and marketing investment. By patient diplomacy, Steyn and Cluver have managed gently to ease the SFW out and replace it with a black investment company.

Already, Thandi is regarded as a role model. Three more companies have set up joint ventures between black workers and their white (liberal) employers. Alan Nelson's New Beginnings, Michael Back's Fair Valley have all been established as a way of giving the black workforce a genuine say in what's going on and a share in the business. Currently, there are some 14 equity-share fruit and wine projects going of which two new ones, Uitzicht (Johann Reyneke) and Geelbekvlei (Andrew Gunn) are just coming on stream.

Cape Dutch cottage, Boekenhoutskloof

Cape Dutch cottage, Boekenhoutskloof

There are further variations on the theme. Papkuilsfontein Vineyards (PV), for instance, is a major project bringing together black retailers and the SFW in a £30 m joint venture covering 250 hectares of vineyard. Here the aim is not only to produce varietal wines but to involve black retailers in developing a wine culture among black consumers. Spice Route, which supports the promotion of black winemakers within the industry, is a partnership involving four of the Cape's most prominent liberal producers, Gyles Webb of Thelema and Charles Back (again), along with author John Platter and black pioneer and producer Jabulani Ntshangase.

The government itself is committed to change. On 1 May, it launched a fund of 63 m rand to help set up more projects like Thandi. But it still has to contend with the entrenched old guard which is resistant to change while paying lip service to it. Following the break-up of its monopoly, KWV, which represents South Africa's 6,000-odd (all-white) growers, has given £4m a year for eight years to a new Wine Trust, but it's only now that the Trust is starting develop its more innovative activities.

So far so good. But not all growers anxious to jump on the bandwagon are doing so out of altruism, according to Anton Cartwright of Hamann and Schumann, which assists black farmers and helped broker the Thandi deal. "We're wary of growers waiting to come in on the back of the equity-share scheme," says Cartwright, "because for some, it's a way of getting capital input via their workers". A major problem, he says, is that the 16,000 rand government grant (about £1,600) is nowhere near enough, especially in the Eastern Cape where one hectare of vineyard costs 10 times as much to buy and plant up.

While Cartwright is delighted to see Tesco selling Thandi's wines, he feels that there's a lot going on in some outlets under the banner of ethical trading that isn't up to scratch. Putting Thandi on the shelf alongside wines produced at co-ops with poor working conditions "distorts the message".

Clearly money talks but it's not the answer on it's own. According to Paul Cluver, "You have to bring in new blood, people who think differently, for people to change an in order to break the mould." As the High Commissioner, Cherly Carolus, pointed out at the Thandi launch, "this kind of innovation is needed if we want to modernise the wine industry. The KWV essentially had a stranglehold. The full potential has yet to be unlocked. The notion of empowerment allows people to take responsibility for their own lives.

The 1998 Thandi Chardonnay, £6.99, Tesco, is currently the best of partnership wines on British shelves. It's well-crafted with a nutty intensity of flavour in white Burgundy-style. The Pinot Noir is heavily oaked but not outrageously priced. Spice Route's 1998 Andrew's Hope Merlot/ Cabernet Sauvignon is £5.99, Waitrose and selected Tesco stores. Charles Back's 1998 Fair Valley Bush Vine Chenin Blanc is at Oddbins.

End